Some words on escapism

In 1985 Ray Belknap placed a 12-gauge shotgun under his chin and shot himself, dying instantly. His friend James Vance then took the same shotgun, placed it under his own chin, and pulled the trigger. He survived but was severely disfigured. The parents sued Judas Priest, whose music, they claimed, had mesmerised their sons, encouraging them to take their own lives. They claimed that the song ‘Better by You, Better Than Me’ from the album ‘Stained Class’, if played backwards, contained a subliminal message that sounded like “do it”. It’s no small irony that the track in question was a cover of a Spooky Tooth song about a guy meditating on a fight with his girlfriend.

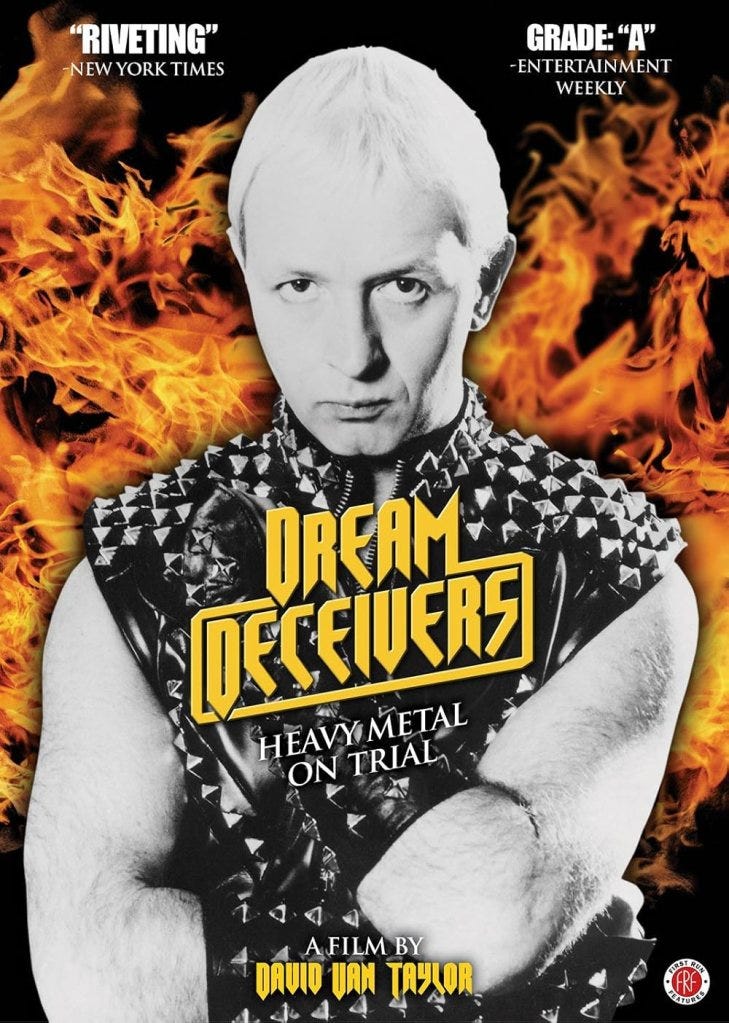

The film ‘Dream Deceivers’ covered the court case that took place in 1990 in detail. It reveals how Judas Priest’s defence lawyers were able to create a profile of Belknap and Vance’s families that showed a highly dysfunctional upbringing, rife with abuse and addiction. Vance, who died three years after the attempted suicide from a medication overdose, is interviewed extensively in the film. At one point he can be heard reciting the opening lines of Judas Priest’s ‘Dream Deceiver’, expressing an almost debilitating desire to be somewhere else, anywhere, just not here:

Standing by my window, breathing summer breeze. Saw a figure floating, ‘neath the willow trees. Asked us if we were happy, we said we didn’t know. Took us by the hands and up we go.

Of course, ‘Dream Deceiver’ itself leads into the ‘Deceiver’ finale, which throws out stark warnings about the price of escapism for its own sake. The metaphorical imagery of the cosmos and celestial bodies framing a refrain of entrapment, of being stuck in a perpetual, disembodied state forever. Once you have “escaped”, there is no turning back.

Belknap and Vance didn’t want to turn back. The escapism they craved was suicidal and absolute. Heavy metal was caught in the middle of parents struggling to reconcile themselves to what their sons had done, their possible complicity in their actions, and a society ill equipped to support or even understand the complex social and familial disfunction that drove them to suicide.

America in the 1980s was still reeling from the counterculture shock of the 60s. Everything from the war on drugs, the Satanic Panic, and the dog whistle racism of “welfare queens” can be read as conservative attempts to recapture control of American identity. It is not the family, schooling, law, or institutional blindness that causes kids to go awry, but some outside threat that manipulates and tempts kids away from the path set out for them by mainstream pedagogy.

The lawyers tasked with defending Judas Priest created a clear separation between their music as an entertainment product and the much more pervasive and immediate realities of family life and schooling for these kids. The nail in the coffin for the case against the band being Halford’s decision to play other Judas Priest tracks to the judge in reverse, and look for random, nonsensical sentences and phrases in the music when played backwards, thus demonstrating the enormous stretch the prosecution was ultimately making in implicating Priest.

Although Vance’s case was an extreme example, for decades metal has been a returning character in moral panics alongside videogames, violent films, and hip hop. More commonly, the vilification of metal rests on the assertion that it's artistically childish, vulgar. The Bill Hicks skit on the Vance case, that the world is two gas station clerks poorer, starkly demonstrates the low regard people had – and still have – for metalheads.

Tasked with defending their cause on multiple fronts, metalheads have somewhat understandably been inconsistent in framing why metal is actually a positive influence in people’s lives, particularly for those struggling with addiction, mental health, and instability. Each new generation of metal has brought different ideas and relationships to the music, and in turn the analysis of how seriously we are expected to take its posturing has shifted. For Judas Priest’s generation, there was little question that the music was “escapist”. Despite its extremity compared to what came before, and the increasingly flamboyant aesthetic adopted by its practitioners (a look famously spearheaded by Halford himself), when asked to defend its legitimacy in the eyes of a confused mainstream, advocates would often revert to “escapism” to rationalise the need for all this surplus activity. Because the concept is self-justifying, the argument is thought to end there. Semantically equivalent to faith, or the phrase “it just is”, “escapism” is the emergency release valve a metalhead can pull on to explain to bemused outsiders why they find such obviously repulsive music so appealing.

As heavy metal gave way to thrash and later death metal the same argument was asked to lift increasingly heavy weights, until the opera of suicide, murder, and arson that was black metal exploded any illusions that these kids were merely “escaping” from a daily reality. The discourse on how to “deal” with black metal ever since has been heated and significant.

As well as being self-justifying, “escapism” could be read as a slur. A piece of art is said to be escapist if it holds no value beyond idle distraction. It helps the individual forget about their daily woes for a time. But it communicates nothing of substance about the world, our lives, or society. Art that has nothing but escapism to offer is no more valuable than a game of Tetris. This argument serves the competing interests of the intellectual and the metalhead. The intellectual is free to dismiss art they regard as vulgar without having to engage with it on any meaningful level. The metalhead, in the face of attacks from concerned parents and teachers, is able to wave their hands innocently and claim that it’s nothing but harmless distraction.

The 21st Century has complicated the picture. Daily life has become harder and more complex for a much broader demographic of people. The Century that was ushered in with the enormous popularity of the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter films saw “geek culture” at large become mainstream. Everyone, it seemed, craved idle escape. And with it, the problematic elements of these previously male spaces floated to the surface. Running parallel to this, the tone of the conversation around mental health has shifted dramatically since the 1980s. Everyone acknowledges its complexity and urgency, but consensus on causes and solutions remains elusive. Metal’s shift from villain to hero in this story has also been widespread and dramatic. But it’s a heroism still premised on the idea that metal isn’t saying anything meaningful - and therefore potentially disruptive - about society. It is, at best, a means of self-therapy. The escapism of metal allows adults to play, explore other worlds, exercise their imagination, but very rarely confront in a manner that would be considered "mature".

Unsurprisingly, Tolkien wrote extensively on this topic in the face of the fierce criticism he received from a snobbish literary elite decades before. He argued that escapism allows people to step away from transience, providing lucidity on more lasting values and purpose. It provides people with a vehicle to use their imaginations to conceptualise a better world, to not accept reality as it is. Ultimately, he argued, there is a heroism to escapism. This is contrasted with desertion, which is escapism taken to excess, an avoidance tactic that could even be characterised as addiction.

There is no doubt that metal rides the line between these two poles. At one end, it provides a healthy outlet to exercise the imagination which, at its best, morphs into an external critique of aspects of society that too often go un-interrogated. At the other, it cultivates traits that could be read as addictive, or at the very least as avoidance tactics. Looking at the rise of “cosplay” metal, with a plethora of bands donning outfits more suited to Hollywood films than a gig, vast fantastical lexicons, and overcooked conceptual material servicing wastefully elaborate sonic statements, it becomes difficult to attach this to any meaningful statement on anything, even as Tolkien envisioned it, seeing adults drift into idle, judgement free play.

He’d had enough, he couldn’t take anymore, he’d found a place in his mind, and slammed the door. No matter how they tried, they couldn’t understand. They washed and dressed him, fed him by hand. I’ve left the world behind. I’m safe here in my mind.

Judas Priest: Beyond the Realms of Death (Stained Class, 1978)

At this point I must confess that I’m about to break character and talk about myself for a bit. I had intended to conduct a deeper analysis on the role of cosplay, or more specifically roleplay, and its possible function as both a useful means of boundary testing in the artistic sense, and the passive cosmopolitan eclectic, superficially picking through imagery and themes to decorate artistic statements that have little to offer beyond filling the airwaves. Unfortunately, some things have happened in my life recently that have rendered me unable to broach this topic with the rigour it deserves.

Earlier this year my wife and I decided that we had come to the end of our marriage. The decision was amicable, but no less painful for the fact. Since that time our lives have followed a cadence of managing the admin headache and cost of divorce, housing and custody arrangements for our two year old son, and breaking the news to family and friends who were completely unaware that we were having problems.

My analysis of why I have been unable to keep my family together has, until recently, been entirely absent for the sake of dealing with the procedural slog of life-admin arising from this decision. I have focused, intensely, on process and legality. But in the last few months the more significant implications of this situation have begun to hit me in unexpected waves. The need to mourn the life my son could have had has become apparent, alongside planning for a new reality, and ensuring that it remains as stable and loving as possible for him.

This has rendered a – hopefully temporary – change in my relationship to music. Metal, whilst still prevalent, has been set aside for the relatively neutral mediator of instrumental electronic music. This has in turn prompted me to interrogate what it is about metal I find so attractive beyond intellectual admiration. Escapism, it seems, is the one thing metal is unable to offer me at present.

My life has been defined by stability, routine, and emotional regulation. It’s had its ups and downs. But through it all I have retained a tense calm in the face of any challenge, personal or professional. Something that is often interpreted as a stubborn stoicism by those who know me best. A refusal to share my inner dialogue even with those I’m closest to. I've had very close relationships with people prone to severe bouts of depression. One of the things I've oddly envied about them is these occasional highs of emotional euphoria they are prone to, something I can only replicate with the help of drugs or alcohol. Mental stability is a double edged sword, shielding one from depths of despair whilst blocking access to boundless highs. In this sense, metal, with all its exhilaration, excess, darkness, and abandon, is something of a defibrillator, shocking that part of my brain that otherwise goes unused. Metal “feels”…so I don’t have to.

This is something that became more apparent after my recent brush with jazz and afrobeat. Based on some of the feedback I received on that essay it seems my comments were interpreted to mean that I regarded it as background music based on its ambiguity, its sleight of hand motion, and transactional, informal flow. Whilst I would absolutely clarify that this music needs to be listened to every bit as closely as metal or classical, my intention in pointing this out was more to highlight that I myself am not up to the task of processing the ambiguity of jazz. The reason I gravitate toward metal, classical, neofolk, and certain forms of ambient is because they make intensive listening so easy. They spell out their precise intention and structure to the listener, allowing them to switch off the part of their mind trained to read implication and inuendo. The feelings of metal are complex but also obvious and provocative. Provocations I’ve come to realise I rely on as someone not prone to outbursts of emotional excess.

I get the impression that my experiences are rather common. The demographic of metal has shifted dramatically since the 1970s. From an energetic, masculine working class to a broader sample of middle class populations who are literally, for want of a better phrase, “having a total normal one”. They are (predominantly) intelligent, in stable employment, calm, steady people.

Recently my circumstances have forced me to process emotions with an intensity I am ill-equipped for. I think this is possibly the reason why I’ve been listening to less metal. This is diametrically opposed to the experiences of Vance and Belknap, whose lives were punctuated by abuse, boredom, and dysfunction, but who found a release and sanctuary in metal so profound it became implicated in their suicidal tendencies. By contrast, I turn to metal when I’m at my most neutral, as a way of forcing some degree of cathartic shock treatment on myself. Others need it as an outlet, a place that reflects the desperation of their circumstances or mental state.

Staring so intensely at my life, and realising that the tools I have in place to process certain things are not up to the task, is an experience I don’t wish to repeat anytime soon. The irony of sharing these thoughts with random strangers online is not lost on me. But it feels like common sense to use any outlet you can. A hobby, if you will. Between a busy job, managing a divorce, and being a father, this has been a challenge. And my usual recourse to thinking and writing about music has offered little joy. Writing an extended tract on metal’s “cosplay” problem has never seemed smaller and less urgent these last few months. But it has been interesting to realise that I’m asking music to perform different functions recently. Right now I don’t need it to present me with complex, multifaceted structures requiring intense study and critique. Equally, I don’t need it to distract me from life. It just needs to permeate my surroundings and remind me that everything is transient.

I think this is also because art is not a coping mechanism, and escapism should not primarily be understood in terms of "coping". Art is an expression of humanity, and is as diverse, messy, and nebulous as this vaguery implies. The electronic music I've recently been imbibing - Orbital, The Orb, Tangerine Dream, Aphex Twin etc. - certainly has, prima facie, only an incidental relationship to emotional catharsis. But I have found it there regardless because the music is so conditional, it moves, it passes, it remains in flux. Metal, at least many of its most lasting works, builds itself around a theme, a central pillar, a sense of permanence. Of course it builds transience around this foundation, but it does so as a means of contrasting this state of flux with an interrogation of "deep time", the eras and eons that pass without noticing the microcosms of human affairs. And that's why at present it's not speaking to me like it used to. I suppose I'm asking of music a particular thing, reassurance that this, too, will surely pass.