The noise diaries XIII

Sunbathed slime

March is an odd time of the year in England. Daylight bulges. The interval between dawn and dusks sags alarmingly. As if saturated by the merciless spring rain beating the ground with violent regularity. But this emergent excess of sunlight reveals a world still utterly dead and utterly miserable.

Decaying leaves continue to litter the ground, their comforting rich browns having long given way to a drab grey. The buds of trees visible only on close inspection. Meaning that any panoramic survey of the landscape reveals nothing but skeletal, haggard forms, twisted organic bodies still reeling from winter’s oppressive dark. A horror made all the more vivid by the rich surplus of daylight.

A few limited patches of precociously eager crocuses and daffodils bring little joy. Even the green of the grass is shrouded in layers of melancholic dew. A grotesque malaise of dull matter stretches before us in the sun. The only respite from this eerie juxtaposition is the knowledge that the trees will soon blossom, flowers will awaken, and a low hum of bees will once again accompany the morning’s toil.

As I yelp in disgust at the desolation of my newly revealed surroundings, my listening habits take on an equivalent sense of panic. The sun may be present in spirit, but its heat is found wanting. This precludes me from adding death metal’s big hitters into my rotation. Incantation or Deicide always felt more befitting of high summer to me, their claustrophobic surpluses of noise furnishing me with a coping mechanism for a season I am ill suited to.

Yet black metal, outside of the brighter, lighter folk and ambient variants, doesn’t quite capture the surreal discomfort of moving through the vibrant greys of a yet to be born world, illuminated by an obnoxious sun. Black metal, as a result, retreats once again into a nocturnal pursuit. For me this means abandoning it entirely for a time. I continue to be disbarred from doing anything other than sleep come nightfall given my son’s newfound penchant for pre 5am starts.

The only option available is to embrace the chaos. Mainlining techdeath it is then. Outside of inevitable encounters with bands formative to or somehow “transcending” the style (Suffocation, Gorguts, Nile), I’ve long regarded this subgenre with suspicion.

A suspicion largely driven by the kind of people that are drawn to techdeath. They always give the impression of doing metal “wrong”. They seem to favour anime over literature, Suicide Squad over Lord of the Rings, they play “video” games, wear branded energy drink merch, their favourites colours to mix with black are purple and lime green, they unironically parrot internet slang in real life conversations. But strange times call for strange decisions. I’ll readily hold my nose and give techdeath another chance to avoid the miasma beyond the window.

And why not start with one of its most divisive practitioners. When approaching a seasoned band with a bulky discography under their belt, it can sometimes help to focus on one album and refuse to move on until it could be considered digested.

A cursory glance at Origin discourse online will tell you that ‘Antithesis’ seems to be the album where they really found their footing, an appropriate place to start. So I selected the previous effort ‘Echoes of Decimation’ to set up camp. Skirmishes into the follow up can wait until after this is published.

At precisely this time of year, for at least the last three years, I’ll drink my annual Guinness and throw on Origin’s third. This and the two albums preceding it seem to just really rub fans up the wrong way, and I’m a sucker for a polariser.

I can, to be fair, see why people are a bit upset about this one. Origin, my guys, what you’ve done here, this is a truly outrageous thing to do to music, even if we allow for your techdeath handicap.

But it’s this excess, notable even amongst its peer group, that keeps me coming back to Origin. I’ve tried rolling in the muck with Necrophagist and Deeds of Flesh, but Origin take it just that little bit too far, asking of the listener – the non-Monster branded trucker cap wearing kind – a near total rewiring of their brains to take in. Indeed, one must almost forget how to listen to death metal to even contemplate this album.

Let me clarify because I’m actually being serious here. Bog standard techdeath, and one of the reasons it’s never appealed to me aside from the degeneracy of its fanbase, is essentially the art of getting less from more. The riff density is higher, the average tempo inflated, transitions more frequent, information flies in all directions, it demands a degree of concentration for a payoff far lower than its austere sister genres.

I’m more than happy to focus on complex music if the rewards are there. But the amount of effort techdeath requires to both actually play and take in as a listener constitutes the very definition of diminishing returns. ‘Onward to Golgotha’, by contrast, through its chasmic spaces, droning chords, and cumbersome flow, conveys far more than anything of value dribbling through the cracks of ‘Onset of Putrefaction’.

But Origin take even this bloated prospect that bit further. The Jenga tower finally collapses. ‘Echoes of Decimation’ is no longer a different expression of the same “type” as ‘Onward to Golgotha’, it moves into a separate category entirely. The speed, excess, flair, and relentless flow of stuff across its brief runtime actually brings this closer to something like Venetian Snares. The whole point is density, disruption, irrationality.

The substance beneath, the stuff I would usually focus on as a death metal listener, blitzes past at a pace I am incapable of ingesting. But ingestion is not the point. There is a transcendent flow to this material, an energy freeriding on the violent exchanges between guitar and drum, weaving its ways across the labyrinthine tapestry of each piece. An almost pre-conscious will, surfing the waves of momentum that ruthlessly drive, nay, pull the music forward. Any scraps of “traditional” melodic phrasing one is lucky enough to stumble upon – the finale of ‘Debased Humanity’ for example – are mere bonuses to this backbone of concentrated physicality. Something one consciously chooses to have delivered directly into the bloodstream by spinning this album.

Given the seasonal flux, there is a serendipity to the timing of Wardruna’s latest UK tour. Setting the guitars aside for a bit feels like an appropriate lever to pull on to survive the disorientation. Having just caught them in York, I am reminded of how massive Wardruna have become. Indeed, it is somewhat ironic that the entire wave of Nordic folk seems to be the biggest “metal” export to reach a general audience in the last twenty years or so.

Whether it’s entirely fair or accurate for metal to claim ownership over this genre is beside the point. Although the crowd in York was predominantly plucked from various “metal” subcultures alongside the garden variety geeks and pagan fetishists. There are very few metal bands that formed this side of 2000 who could reliably fill venues the size of the York Barbican for an entire tour.

Since the early 90s and the inception of black metal, metal has cultivated a healthy underbelly of ritual ambient, martial industrial, and neofolk. But it was always treated as something of an appendage. Relegated to the side projects of metal artists, amateurish, lo-fi, and largely conducted through synths as opposed to real instruments. If only someone would write a book about that.

Wardruna bucked this trend by furnishing us with a more organic, many would say authentic, approach to ritual folk music, with real instruments, and a more scholarly attitude to their subject matter, fleshing out the previously amateur historicism of metal with cinematic flair. They weren’t the first, Hagalaz Rundance, Tenhi, and Stille Volk all come to mind. But Wardruna certainly upped the stakes with professionalism and polish, taking the music beyond mere cosplay and into something that caught the attention of listeners well beyond the borders of metal itself.

The wave of bands that followed in their wake, from Bryrdi to Heilung, Danheim to Osi and the Jupiter, all seem to have captured an appetite for musical heritage blended with postmodernist play, anchoring folk tropes with familiar contemporary calling cards in a way both comforting yet humbling for a modern audience. This is in direct contrast to earlier neofolk in Sol Invictus or Death in June, which, in this older incarnation, tried to reinvent folk music in a post industrial environment through the conscious deployment of artificial instrumentation alongside the acoustic, thus slotting a folk sensibility into a synthetic age that claimed to have dispensed with the need for such sentimentality.

That being said, Wardruna, as the biggest and one of the earliest to capture this later wave, are the most obviously enamoured with their source material. Indeed, in a brief speech at the end of their set in York, Einar Selvik offered a gentle rebuttal to anyone (myself included) that has questioned the authenticity (or even possibility) of their interpretation of “Viking” music over the years. Whether accuracy was ever his intention, he claimed, is really beside the point, the connection to nature as a source of inspiration remains a common thread, as does the impulsive need we all have to partake in music.

These words certainly resonated with a handful of drunk Northerners, but whatever truth there is in them, it’s maybe for this exact reason that I’m drawn more to an album like ‘Skald’ or the debut ‘Runaljod – gap var Ginnunga’ than the full frontal orchestral assaults this band became known for.

For long periods of Wardruna’s music the word “folk” doesn’t really get a look in. The experience is too…experiential, the delivery too panoramic. The joy to be harvested more akin to a soundtrack than music for its own sake. Not that it’s any less enjoyable as a result. I’d wager it’s the immersive pulses of atmosphere alongside the sharp musical signatures of Selvik – not the least of which is his own voice – that has brought his work to such a wide audience (alongside TV appearance on ‘Vikings’ of course).

Whatever the reason, the enduring popularity of Nordic folk, not least within the metal community itself, speaks to an underlying suspicion I’ve long held that people are increasingly only willing to engage with metal once removed. Losing interest in the guitar altogether, they will seek experiences that feel more grounded, authentic, and somehow more connected to the grass we are constantly instructed to touch.

Lastly it would be untoward if I didn’t discuss Stephen Hough’s recent performance of Liszt’s Paino Sonata in B minor I witnessed as part of the Leeds International Piano Series. It’s a piece I’ll freely admit to being somewhat beyond my abilities as a listener, but it nevertheless prompted me to dig out my copy released on Naxos Records, recorded by the label’s house pianist Jenő Jandó.

As a younger listener I wasn’t such a fan of Jandó. I have other Naxos recordings of his, namely various Bach keyboard works and Beethoven’s first three piano sonatas. All are dazzling for their precision but seem to lack the soul and character of the louder voices of mid-20th Century classical piano.

That being said, for a work as bloated and bipolar as Liszt’s piano sonata, a little clarity goes a long way. Aficionados of this form will tell you that conventionally a sonata is made up of three or four movements. The first of which will introduce a theme, also called an exposition, then a development, followed by a recapitulation, much like a clearly structured essay perhaps. The following two or three movements will cycle through a slow section (usually recognisably lyrical or ballady to modern ears); a dance section, usually shorter and choppier; and finally a…finale, a balls to the wall riot of speed, extremes of pitch, volume, and complexity.

Liszt bucked this trend by writing his sonata as one continuous piece of music (roughly half an hour in length depending on the performance), bringing this closer to the Fantasies of Schumann and Schubert. But he also smuggled a covert sonata (or two separate sonatas depending on who you ask) beneath this carefree facade.

But all this subterfuge hardly jumps out if one goes in blind. Whilst the rigid structuralism of a two-dimensional sonata masquerading as freeform spontaneity is all terribly clever, what’s a layman to do with this information? Well, understand the sonata and understand Liszt would be my recommendation. The former you can do without studying a single piece of theory. Just spend time with some choice cuts from Beethoven’s 32 sonatas (I’d nominate numbers 1, 2, 3, 8, 14, 17, 23, 29, and 32 as a starter for ten).

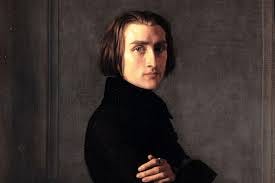

Next, understand Liszt. Why? Whenever one reads up on the towering figures of music, art, and literature past, one will often encounter the phrase “x died in obscurity”. Liszt was not one of those figures. He was perhaps the biggest rockstar of the 19th Century. A virtuoso (and devilishly handsome) performer, he relentlessly toured Europe throughout the middle of the century, generating a phenomenon mirrored a little too perfectly by Beatlemania a century later. He was also the centre of a social circle that included the likes of Chopin, Robert and Clara Schumann, and Wagner. He was, in many respects and beyond his stature as a composer, the popular face of the formidable Romantic period at the height of its creative intensity.

Along with this fame and bravado, he was arguably one of the most artistically daring of his oeuvre. His Piano Sonata, in true Romantic fashion, spits in the face of convention whilst still toying with its raw materials. It can be quite unlistenable for its aggression and slow devolution toward the chromatic, only to shift to moments of unprecedented tranquillity.

Even a sonata virgin will pick on its wild mood swings. Decorative and flowery material gives way to atonal barbs, jagged chords requiring of the performer a violent touch, punctuated by trickling flows of arpeggios, fragile in their briefness. The swaggering disregard for convention finally hammered home by the close of the piece as it drifts away with a slow, hesitant, unresolved drone of chords, eschewing the decisive finales of the traditional sonata (and symphony) form.

In this respect Liszt proved that he was not only the most well known composer of the Romantic era, but also the one most alive to its possible futures. It’s precisely the atonality, dissonance, variety, and sheer breadth of expression he evokes across this piece that would be picked up on by the late Romantics and into early modernism. A piece that retains the strict adherence to the musical architecture established by Beethoven, whilst conjuring ample space to expand on these spontaneous, outrageously emotive flights of fancy. An eye on the past and a window into the future. I’d speculate that it was only Liszt’s status as a touring rockstar that afforded him the creative space to engage in these experiments.

The idea that music comes with required reading and foreknowledge is distasteful to a modern audience. Music should speak for itself, it is claimed. The reason music overwhelms us in youth is precisely because we experience it “raw” so to speak. We are defenceless in our ignorance and so it casts a spell on us that is difficult to recover from. A spell we crave in later life as age and knowledge burden us with an inability to just enjoy things. We collapse in nostalgia. But it is equally true that, particularly with classical music, a little knowledge can go a long way. Our tastes may lose the spontaneity of adolescence, but they bank a longevity, nuance, and direction as prerequisites for inculcating music into the soul. A small toolkit will aid the casual listener in navigating its many moving parts, its sequence of events, ensuring that one is not overwhelmed or alienated by the music as I am alienated by the dim, slimy landscape revealed to me by the March sun.